The Secret Court of David Stacton

The Secret Court of David Stacton

In 1963, Time Magazine included author and sometimes-historian David Stacton in its list of the best American writers, alongside the likes of John Updike, Joseph Heller, Phillip Roth, Bernard Malamud, and Ralph Ellison. These authors were identified as the future of American literature in the wake of Hemingway and Faulkner. (Harper Lee merely got an honorable mention and James Baldwin is only noted through a comparison to Ellison, the only black writer on the list).

Of these chosen authors, several would fall out-of-print or into obscurity. Sometimes both. As is the curious case of David Stacton. Dead by the age of 44, Stacton still managed to pump out more than a dozen literary novels, several books of history (most widely known is his biography of the Bonaparte family, as in, Napoleon Bonaparte) short stories, poems, and numerous mid-century pulp fiction books under various pseudonyms ('David Stacton' is itself a name of his own invention, although the man born as Arthur Lionel Kingsley Evans would eventually adopt it as his legal name, saying it was the one he liked best). Always more popular in the U.K., Stacton was finally gaining traction in his native United States when Time took notice. Five years later he would be gone.

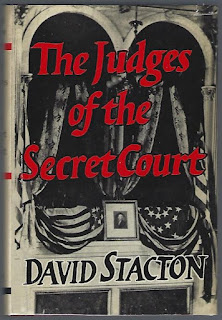

When an artist dies two things can happen. Their stock may suddenly rise or, regrettably, the sun sets on any further critical attention or commercial engagement. Stacton's legacy grew cold in the decades following his death in an Amsterdam hotel in 1968 of a stroke, apparently of natural causes despite his relative youth. His 1950s and 60s hardcovers gathered dust on forgotten shelves until 2011 when The New York Review of Books reissued The Judges of the Secret Court, his 1961 novel about John Wilkes Booth and the assassination of President Lincoln. The editors declared it a "long lost triumph of American fiction as well as one of the finest books ever written about the Civil War." They're not wrong.

This trip to the archives must have proved a success. Soon after, Stacton's original London publisher, Faber & Faber, reprinted most of his literary novels under their "Faber Finds" collection. The collection starts with two contemporary noirs set in or around San Francisco and the Northern California mountains. Faber wanted more of the same, but Stacton had enough self-awareness to realize that his tendency to grandiose themes and melodrama simply "went down better with historical sauce" and he never wrote about his own time and place again.

David Stacton was as close to an 'out' gay man as I imagine possible in the 1940s and 50s America. A penchant for drag personas is reported by contemporaries. In everything he wrote a bold, fearless, but often sad voice emerges. The voice of an outsider who knows exactly why they are not part of society's inner circles. Accepting this limitation on one hand, while plotting dominance through alternative means on the other.

It is not surprising, given the alienation he must have felt , that Stacton was drawn to the inner life of tragic (or perhaps infamous) historical figures and the cosmic events that surrounded and entangled them. There is always a sense of doom and impending downfall that follows his characters even as they seem to be on an upward trajectory. They know inherently that even though the world demands this of them, requires this life of them, it will simultaneously never allow it.

I'm an avid reader and always have been. I discovered David Stacton completely by accident, or maybe one can say it was serendipity. A trip to Munich and a visit at the incomparable Neuschwanstein Castle of King Ludwig II of Bavaria inspired research for a never-realized book I fancied I would someday write about the "Mad King". (I did write a killer prologue and epilogue for my abandoned novel - perhaps to be shared at a later date, reworked as a short story). But if the time and effort invested in that temporary fixation did anything it was to lead me to Stacton's own novelization of Ludwig's final years, which he titled Remember Me.

I immediately wondered why I did not, in fact, remember any writer named David Stacton. Indeed, I don't think I had ever encountered the name at all. No matter. By the time I was done with the book, or perhaps even Stacton's prologue to the book, I was a fan. That this writer was obscure (to the general public, at least, and even to many fiction lovers like myself) only piqued my interest. I've always been fascinated by the concept of kindred spirits. What they are and how we find them, and why. Do we invent them as needed? A thought for another time.

In Remember Me, Stacton would describe his attraction to the Ludwig myth in a way that reverberated through me and still leaves a electrical charge:

It sometimes happens that when we can find no comfort among the living, we turn for advice to the dead. Most of us have friends in history. But the dead are eager for life. As soon as they sense our sympathy, they invade us and take us over utterly, until we can no longer tell whose life we are living, ours or theirs. Yet the tyranny of history is not without certain benefits. It can teach us wisdom. It can soothe us tenderly. It can console us for the burden of ourselves.

I soon collected more of Stacton's work, taking great enjoyment hunting down original copies, sometimes signed by the man himself, throughout the English-speaking world. Nothing is truly lost and the internet, for all of its evils, allows us to find whatever hidden treasures for which we search. (The title of this blog even takes its name from Stacton's final unfinished manuscript, Restless Sleep.)

The broad range of historical characters and events covered in Stacton's novels show a man whose view was utterly bent on finding universality. From Ancient Egypt to Medieval Japan to the Spanish Conquest of the Americas, Stacton claimed his books to be part of a larger series, no matter how disparate in time and space they may seem. He sought the biggest events in history then subjected its actors to intense scrutiny of the heart and mind to reveal what made important people tick. The most succinct statement of his intention may be found in A Dancer in Darkness, a novel about the Duchess of Amalfi:

The one thing kept from the masses is that the great ones of the world are freaks. They have been so pulled about by eminence that they no longer have a shape of their own. Greatness is a cancer.

Comments

Post a Comment